Could traditional architecture offer relief from soaring temperatures in the Gulf?

Temperatures in the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq and Iran could soar to uninhabitable levels during the course of this century, according to a new study.

Already, places such as Al Ain and Kuwait can experience temperatures of up to 52℃. But the study predicts that the effects of global warming and the increase in greenhouse gases could push the average temperature up to the mid 50℃s or lower 60℃s.

Currently, many residents of the gulf can find refuge in air-conditioned homes, shopping centres and cars. But as temperatures increase, so does the need for cheaper, more sustainable, less energy-intensive ways of staying cool. Fortunately, the region’s past offers a rich source of architectural inspiration.

A history of heat

Historically, the inhabitants of the Gulf were either farmers living near oases in agricultural villages, Bedouins living in tents in the desert, or urban dwellers living in cities. Given the global trend toward urbanisation, it makes sense to take a closer look at how the latter group coped with the heat.

Traditional buildings in the gulf’s cities and villages are designed to maximise shading, reduce thermal gain of the sun radiation, regulate building temperature and enhance air circulation. These effects are achieved through a clever combination of building materials, placement and design.

Natural materials such as limestone and mud – in some cases mixed with local desert plants – provide a construction material with the capacity to regulate building temperatures. The material itself is capable of absorbing moisture in humid conditions, which can later evaporate during hot and sunny days to provide a slight cooling effect. And the sandy texture and colour of the buildings reduces both the absorption and emission of radiating heat.

Traditional buildings are placed adjacent to one another, with narrow roads and alleyways in between. This means that the ratio of the area exposed to the sun relative to the building’s total volume is minimised, which in turn limits heat increases during the day time.

Many traditional structures feature an internal courtyard, often containing trees and a water well. The courtyard is typically surrounded by rooms or walls on all sides, maximising the area in shadow throughout the day and creating a space for socialising in the evenings. When the sun bears down at midday, the courtyard works as a chimney for the hot air to rise and be replaced by cooler air from the surroundings rooms – this promotes air circulation and creates a cooling effect.

Glass is not a common material in traditional buildings. A typical room has two external windows: one very small window, located high up the wall, which is kept open to allow air to circulate and let in natural light. The second is larger, and closed by wooden shutters, with grooves to allow the flow of air inside the room while maintaining privacy. Rooms also have windows towards the internal courtyard for improved cooling. Finally, a mushrabiya – a projecting window with carved wooden latticework, typically located on the upper stories of a building – allowed for better air circulation and a view.

Some buildings also have a wind tower, which creates natural ventilation by circulating cool air. The narrow streets allowed them to be covered in most cases by light material from date palm trees to avoid direct sun light. This allowed for better air circulation between streets and courtyards of buildings, via the rooms.

All of these features helped to keep traditional buildings cool. But the question remains, how can we apply them in today’s cities?

Hot, modern buildings

Modern buildings in the Gulf are built predominantly from reflective glass, concrete and asphalt, which means that temperatures really soar during day time, due to high reflection or high absorption and emission of radiated heat.

But with research and improvements in building and pavement materials, designs, urban planning, insulation and the use of renewable energy, cities in the Gulf could maintain a comfortable lifestyle, with a lower level of carbon emission and fossil fuel use.

For example, Masdar city in the United Arab Emirates has attempted to combine some of the lessons learned from the past with modern technologies by increasing shaded areas, creating narrow streets and constructing a wind tower.

The use of insulation would also reduce the need for air conditioning and lower electricity consumption. Meanwhile, natural or new materials which absorb moisture and increase thermal capacity (meaning the material can maintain lower temperatures in higher heats) could regulate heat gain and facilitate the natural cooling process.

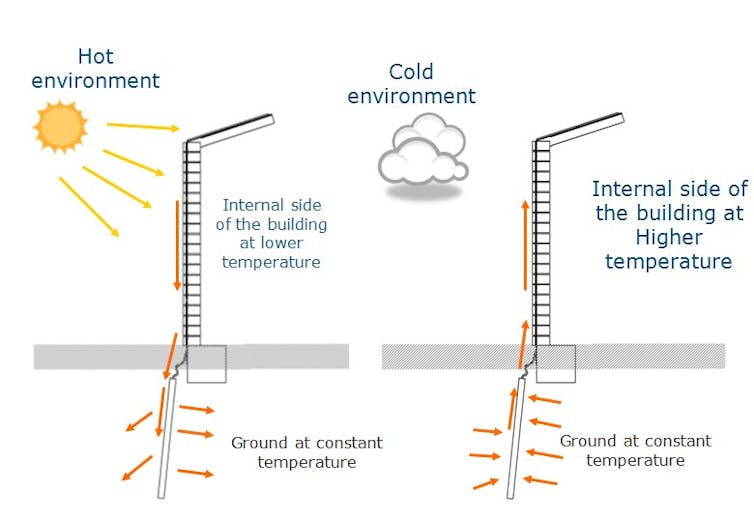

I have developed a new patented technology to regulate building temperatures in extremely hot conditions using a heat sink in the ground. The heat sink will allow the ground to exchange heat with the envelope of the building, thereby reducing its thermal gain on hot days.

In recent years, the Gulf countries have sat up and paid attention to renewable energy and sustainability measures. Research and development is expected to progress further in this area if people are to live comfortably at the expected high levels of temperature, while reducing their dependency on fossil fuel consumption and carbon emissions.

Read more: Adrian Pitts, professor of sustainable architecture at the University of Huddersfield, looks at the impact on cities.![]()

Amin Al-Habaibeh, Professor of Intelligent Engineering Systems, Nottingham Trent University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Comments